Time Passing: A Conversation with Valérie Perrin

‘I wanted to examine old age through the eyes of youth, seeing what age could bring to youth.’

Image Credit: Valentin Lauvergne

First, I wanted to ask you about your journey as a writer and now a widely published author?

I feel very happy, but even the word ‘happy’ isn’t quite strong enough to describe the joy that I’ve felt the past few years. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, but since Fresh Water for Flowers became an international success, my life has completely changed. This gave a boost to Forgotten on Sunday, which has been rediscovered in many countries, and has also given incredible opportunities to Three. Despite all this joy, there is inevitably a lot of pressure on my next novel, but I imagine that is normal. Each time I write a novel I am filled with nerves, and it feels as though it is my debut all over again.

How has it felt to now be published in the UK? And, more generally, what do you feel is the significance and importance of your book – and other books not written in English – to be shared with a much wider audience? Did you ever feel hesitant about any cultural details not being translated or understood accurately?

It’s wonderful. Fresh Water for Flowers and Three are already published in the United Kingdom, and it’s amazing to me that my first novel has now joined the other two in English. I am thrilled that Forgotten on Sunday will be published in English. It was the first in my writing journey, I put everything I loved into this book – dreams, birds, elderly people who are far from healthy. I put in each of my obsessions, and I even spoke about my grandparents in it. A first novel is never innocent, as I believe they speak of the obsessions that follow us through life.

For readers who haven’t yet read your work, could you summarise the plot of Three and Forgotten on Sunday and also maybe tell me a little bit more about your process and the inspiration behind each book?

To start writing, you need a spark. For me, and for Forgotten on Sunday, the spark was the absolute necessity to write a story. Once I’d finished writing it, I thought it would be my only book, as I lived many lives before becoming an author. I didn’t imagine that I’d write two or three novels after.

Forgotten on Sunday is a book that I wrote at the end of 1999 and beginning of 2000. It was a story narrated by a seagull and told the story of a couple: Hélène and Lucien. Hélène lived in a nursing home, lost in her own imagination, and Lucien, her lover, was trying to bring her back to reality. Time passed, and I carried this story within me until 2007, when I decided to dive deeper into the story and add the character of a carer, who ended up becoming the protagonist, Justine. She became the narrator of Hélène, Lucien, and the seagull’s story. This was the starting point.

I worked with a young carer for a long time, a friend’s daughter who looked after elderly patients. I read her extracts from the book, and she told me about her day-to-day in the retirement home. Once her work routine had been sorted, I developed a plot based on her profession – the love story of Hélène and Lucien, an elderly couple in the nursing home where this young carer worked. The father of my children is a physiotherapist, and he often worked with elderly people in retirement homes. As soon as he’d return home after work, he would share his thoughts with me. In fact, ever since I was young, I’ve had a fascination with the elderly. They are filled with memories, and I think it’s important to leaf through their memories before they depart. This is another of my obsessions.

I felt a deep sadness and melancholy after writing my first book, and then I met Violette in a cemetery. When my readers finished Forgotten on Sunday, they asked me to continue writing. I soon realised that Violette would be an important subject, and so I decided to write Fresh Water for Flowers. As for Three, I’m a believer that we carry books within us, even if we don’t know it. Reading Phillippe Besson’s Lie with Me was the spark that inspired me to write Three. I wanted to write about youth, childhood, and the successes and disappointments that arrive when we are 40 years old.

Three is a story about thirty years of friendship, love, dreams, and secrets. The story takes place in 1986. Adrien Bobin, Etienne Beaulieu, and Nina Beau are in their final year of primary school. By chance, they are all placed in the same class, and they become dependent on one other. From frivolity to their ever-changing bodies, school buses to night clubs, blood vows to adult life, they stick together through their years of high school and sixth form. It is a promise that keeps them all together: they will all leave their provincial town to live a new life in Paris, where they will make music and never leave each other’s side. We meet them again in 2017. A car has been pulled up from the bottom of the lake in the small town where the three friends grew up. Virginie, a freelance journalist with an enigmatic past, covers the story. She knew the three friends very well. What is the link between the car accident and this powerful story of friendship? It’s a story of childhood and the passing of time separating friends.

Each of my books were written three years apart, as I spend a lot of time writing my books, which are very structured, built much like thrillers, and take a long time to put together and articulate.

Talking specifically about Three, I absolutely loved this book, particularly the changing dynamics between the three main characters. Our guest editor of this issue, Lydia Sandgren who wrote Collected Works, has actually spoken about the specific dynamics that an author is able to explore when there is a triangle of relationships at play – could you tell us a little more about your decision to focus on three people and whether you agree that this dynamic is particularly fertile ground for literature?

I think that what is fundamental in Three is the fourth character, the narrator. She is the one who speaks in the present. I wanted readers to ask themselves why and how she knew the three friends so well. It’s as though she is a spy within this friendship triangle.

Being inside the head of these four people, two boys and two girls, seeing their choices, taking the time to develop their experiences of high school and sixth form, and seeing what happened, was important for me. Like my characters, many teenagers are forced to leave the small towns they grow up in. This is a subject that I’d held an interest in for a long time. I followed the same journey that they did, I left the provincial town. I also wanted to speak about the brutality of finding oneself alone in tiny little studios in a big city after growing up in a protected space on the outskirts.

Three was very important for me as it allowed me to follow the characters throughout the entirety of their lives. Readers have told me that I brought their ghosts to life, reminding them of childhood friends, and the parents of their friends. What’s important is this friendship triangle and above all, the narrator, whose story we discover at the end. What’s important is the thriller that looms in the background, with that car dredged from the bottom of a lake that one of the three friends swam in as a child. Also, the big question that we ask ourselves from the beginning, which rears its head in the past, is why the three friends no longer speak to each other, after having been so close for so long.

Your books all balance style and plot beautifully, with both aspects of the book feeling as well thought out as the other. Was this something you considered before you began writing?

I come from the world of cinema; I started as a screenwriter. My books are like screenplays, filled with dialogue and I often set up very visual exchanges because I come from the world of photography and screenplays. My books aren’t too different from films, and wouldn’t be too hard to adapt to film, as they are very dense, with a developed setting, and they are scripted with their dialogue. I think in terms of cinema when I write, as though I am holding my camera and filming the characters and their spirits, in the past and the present. Also, I don’t know if other authors do this, but I act as though I’m a journalist before I start writing. I ask questions to people working in the profession of my protagonist. It’s so important to ask questions to find the truth about people and their day-to-day lives, and the situations that I will cover in my novels.

In terms of timelines, it seems that you are drawn to epic timelines that span great lengths of time. And do you particularly enjoy exploring the growth of characters and the ways in which their past influences and affects their futures?

Absolutely. I love Forgotten on Sunday, as it takes place over a century. The story unfolds from 1919 to 2013. Actually, I was very interested in these temporalities, these people, and I wanted to examine old age through the eyes of youth, seeing what age could bring to youth. The life of our heroine isn’t easy. Also, I love intergenerational stories.

Your characterisation is incredible and very complex – how did you approach the challenge of embodying both male and female characters and characters of different ages in your books?

I owe it to cinema, having written for actors like Jean-Louis Trintignant, Johnny Hallyday, Sandrine Bonnaire, Jean Dujardin, actors of all different ages. I had to put myself in their shoes to write their scenes and their dialogue. You take on the age of the man or woman you are writing, and that helped me a lot. I have this ability to entirely – physically and intellectually – step into the shoes of both a child and an elderly person. I’m able to feel their emotions, no matter their age or social class.

Which other authors inspire your work, both thematically and stylistically?

It’s inevitable that people influence me, and I pay homage to them in my books. I always bring my beginnings back to the book From the Land of the Moon by Milena Agus. I think that it’s the book that most helped me in taking the first steps to writing Forgotten on Sunday. It’s the story of a young girl who speaks about the grandmother that she loves. It’s a sensual and powerful novel, filled with love. It’s a complicated story about a young girl. I am sure that it was the book that allowed me to break through the barrier and write.

Are there any books have you read and loved in French that you would implore British publishers to translate into English?

Of course! Les Déferiantes by Claudia Gallay, which is one of my favourite books. Ensemble, c’est tout by Anna Gavalda. Le gout des poires anciennes by Ewald Arenz has had huge success in Germany and is very sensual.

And lastly, do you judge a book by its cover?

It can influence me. I recently bought a book solely because the cover was absolutely sublime. I’m unable to resist buying a book when I walk into a bookshop, and if the cover is beautiful, it is difficult to walk out without buying all the books. Also, I never read the back cover, instead I read the first page. The first page is what makes me want to read the book, or not! I only read the back cover when I’ve finished the book, to see how they summarised it. I don’t like it when someone tells me what happens in a book before I’ve read it.

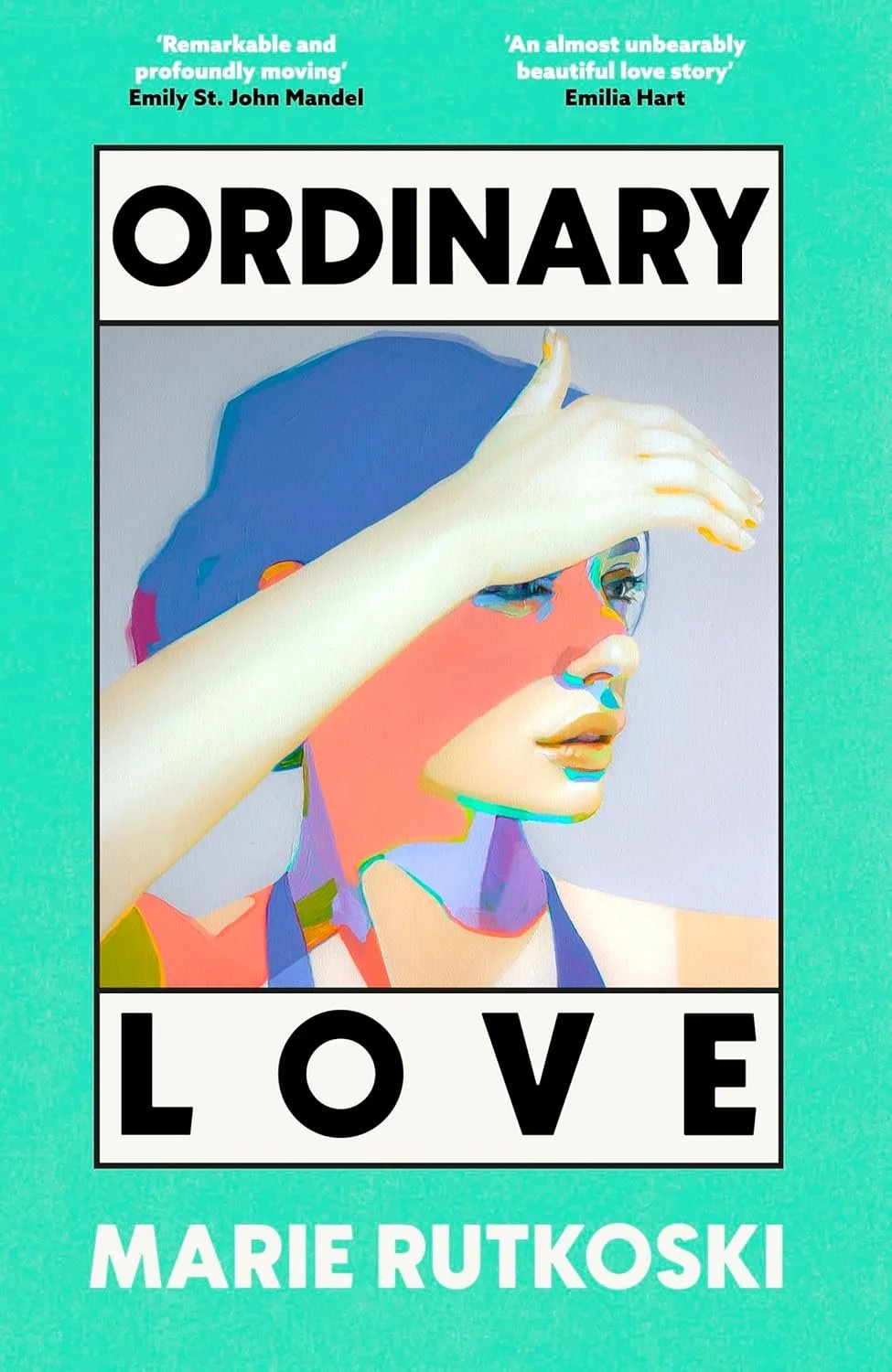

Editorial Picks